Microsoft and Apple have been business partners and tough competitors for many years. Back in the seventies, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates worked close together. In 1997 the Windows-manufacturer helped Steve Jobs saving Apple.

In the early seventies, there was no such thing as a personal computer. It took geniuses and visionaries like Steve Wozniak and Bill Gates to invent this new industry. The early computer geeks were energized by the arrival of the January 1975 issue of Popular Mechanics, which had on its cover the first personal computer kit, the Altair. The Altair wasn’t a real computer —more a $495 pile of parts that had to be soldered to a board that would then do little—but for hobbyists and hackers, it heralded the dawn of a new era. Bill Gates and Paul Allen read the magazine and started working on a version of BASIC, an easy-to-use programming language, for the Altair. It also caught the attention of Jobs and Wozniak.

Later Steve Jobs had to ask for the Microsoft BASIC because his friend Wozniak didn’t finish his own version of BASIC for the Apple II. “He was very childlike,” said Jobs later to the author of his biography, Walter Isaacson, about “Woz”. “He did a great version of BASIC, but then never could buckle down and write the floating-point BASIC we needed, so we ended up later having to make a deal with Microsoft. He was just too unfocused.”

With the rise of the Apple II in the late seventies, Microsoft became more and more successful – even before the IBM PC was invented. When Apple developed the Macintosh Bill Gates and his team was the most important software partner – despite the fact that Microsoft was also the driving force behind the IBM PC and the PC clones. And Steve Jobs even invited Bill Gates for the preview of the Mac: The high point of the October 1983 Apple sales conference in Hawaii was a skit based on a TV show called The Dating Game. Jobs played emcee, and his three contestants, whom he had convinced to fly to Hawaii, were Bill Gates and two other software executives, Mitch Kapor and Fred Gibbons. As the show’s jingly theme song played, the three took their stools.

Gates, looking like a high school sophomore, got wild applause from the 750 Apple salesmen when he said, “During 1984, Microsoft expects to get half of its revenues from software for the Macintosh.” Jobs, clean-shaven and bouncy, gave a toothy smile and asked if he thought that the Macintosh’s new operating system would become one of the industry’s new standards. Gates answered, “To create a new standard takes not just making something that’s a little bit different, it takes something that’s really new and captures people’s imagination. And the Macintosh, of all the machines I’ve ever seen, is the only one that meets that standard.”

But even as Gates was speaking, Microsoft was edging away from being primarily a collaborator with Apple to being more of a competitor. It would continue to make application software, like Microsoft Word, for Apple, but a rapidly increasing share of its revenue would come from the operating system it had written for the IBM personal computer. The year before, 279,000 Apple IIs were sold, compared to 240,000 IBM PCs and its clones. But the figures for 1983 were coming in starkly different: 420,000 Apple IIs versus 1.3 million IBMs and its clones. And both the Apple III and the Lisa were dead in the water.

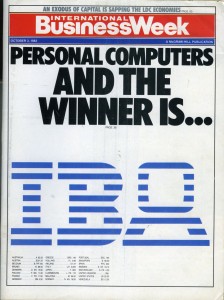

Just when the Apple sales force was arriving in Hawaii, this shift was hammered home on the cover of Business Week. Its headline: “Personal Computers: And the Winner Is . . . IBM.” The story inside detailed the rise of the IBM PC. “The battle for market supremacy is already over,” the magazine declared. “In a stunning blitz, IBM has taken more than 26% of the market in two years, and is expected to account for half the world market by 1985. An additional 25% of the market will be turning out IBM-compatible machines. (Walter Isaacson, p. 159-160)

Apple boss John Sculley’s marketing strategy for the launch of the Macintosh was obvious. The former Pepsi manager, who had been brought to Apple by Steve Jobs, intended to arrange a duel between IBM and Apple, black vs. white, with Apple playing the role of the underdog. Sculley wrote in his book Odyssey:

So we needed a campaign that would focus on a two-horse race to leverage off of Apple’s underdog status. Dozens of other computer companies were coming out with products and I was afraid we were going to get lost in the crowd. If we could create a two-horse race between us and IBM, we might be able to convince people that there are really only two computer companies competing in the marketplace. In any large consumer industry, few people remember the third- or fourth-largest competitor.

In the fight against competitors such as Atari, Commodore, Sinclair and Amstrad, the Apple strategy paid off well. But Sculley, as well as Steve Jobs, had completely underestimated that Microsoft, being an ally from the outset, would, with the aid of Apple, develop into a dominant power of the PC industry and even dwarf IBM.

Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded Microsoft as a small software company in Albuquerque (New Mexico) in 1975 and developed the programming language BASIC for the legendary computer MITS Altair in collaboration with other co-workers. Due to fortunate circumstances, Microsoft landed an order from IBM to deliver not only BASIC but also the operating system for the first IBM PC in 1980. In the negotiation phase, the then-leading operating system manufacturer Digital Research (CP/M) did not want to engage in page-filling adhesion contracts from IBM – and thus lost this gigantic deal.

Microsoft did not have any operating system then, but this did not prevent Bill Gates and his companion Steve Ballmer from playing for high stakes while facing IBM. From their neighboring software shack Seattle Computers (in the meantime, Microsoft had moved to the northwest of the USA) they bought all rights for QDOS (Quick and Dirty Operating System) for no less than 50,000 dollars in July 1981 and renamed it as MS-DOS. Gates had been clever enough at that time not to have all rights to the system negotiated away by the IBM crew and was, therefore, able to win clone companies such as Compaq as customers later.

When Microsoft provided their BASIC for the Apple II, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates constantly ran into each other at that time. “Even before we finished our work on the IBM PC, Steve Jobs came and talked about what he wanted to do, what he thought he could do, sort of a Lisa but cheaper. We said boy, we’d love to help out”, Gates remembers. “The Lisa had all its own applications, but of course, they required a lot of memory, ah, and we thought we could do better, and so Steve signed a deal with us to actually provide bundled applications for the first Mac, and so we were big believers in the Mac and what Steve was doing there.”

Apple urgently needed software for the Mac, as there did not yet exist any program for the new system except for their in-house products MacWrite and MacPaint. Gates promised to have the programs Chart and File written for the Mac in addition to the spreadsheet program Excel. Steve Jobs appreciated the risk Microsoft took, but was not content with the first results though. “Most people don’t remember, but until the Mac, Microsoft was not in the applications business… it was dominated by Lotus. And Microsoft took a big gamble to write for the Mac.”

Apple still could have coped well with having given Microsoft’s new application business a leg up. However, Bill Gates tasted blood in the Macintosh project. Jeff Raikes, who was responsible for the Office business at Microsoft until early 2008, reviews: “And so we got started in early 1982 on our Macintosh software effort and I think at that point in time, you know, it really clicked with Bill that, you know, graphic user interface was going to be the way, the way of the future. But while Bill was having his own GUI revelation, Jobs believed that Apple’s true enemy was IBM.”

Raikes joined Apple Computer as the VisiCalc Engineering Manager in 1980. He worked at Apple for fifteen months before being recruited to Microsoft by Steve Ballmer in 1981 as a product manager. He was promoted to director of applications marketing in 1984 and was the chief strategist behind Microsoft’s investments in graphical applications for the Apple Macintosh and the Microsoft Windows operating system. In this role, he drove the product strategy and design of Microsoft Office.

Steve Jobs didn’t see much risk in bringing Microsoft into the Macintosh project. After all, the division of labor between Apple and Microsoft had worked well on the Apple II. The Apple II used some Microsoft software and Jobs reached out to Microsoft this time too. He didn’t want the company to make the Mac’s operating system. Apple was building that on its own. But he did want it to make stuff like spreadsheet software, and word processing.

Andy Hertzfeld, the technical lead for the Macintosh system software, recalls in the podcast “Land of the Giants” with Peter Kafka: “Microsoft was the first Macintosh developer. There was a partnership relationship from the very beginning between both companies. We needed to recruit the right partners that had both the technical skill and the vision to want to write software for the Macintosh. So Microsoft was the very first company we recruited.”

But Hertzfeld thought Microsoft wasn’t just going to be a partner. He thought Bill Gates was going to be a competitor too. “So I picked up on the idea that maybe Microsoft was besides writing applications, they were going to make their own version of the Macintosh. Seemed pretty obvious to me.” One of the guys on Microsoft’s Mac team was asking many questions about the Mac’s guts. He probably didn’t need to know this stuff to make software for the Mac.

Andy Hertzfeld: “I told Steve about it. He kind of laughed it off at first. He thought Microsoft didn’t have the skill to be able to do that.” Steve Jobs was half right. Microsoft didn’t create its own Macintosh. Instead, it created new software that turned other people’s computers into a sort of Macintoshes. And he used that same idea for a graphics-based interface. Gates it turned out had seen what Xerox Park was doing too. He unveiled his plan a few months before the Macintosh debuted.

Andy Hertzfeld: “In November of 1983 they announced their first version of Windows. Steve freaked out. He goes: ‘Get Gates down here right now.’ And I was thinking how are you going to do that? But like in a matter of hours Bill Gates was there. Steve just screamed at him. But Bill’s credit: he just listened to Steve scream and finally responded with a fairly famous response about where Steve said: ‘You’re ripping us off, you’re ripping us off’. And Bill said something like: “Well that’s not how I think about it. It’s more like we both had a rich neighbor named Xerox and you went in to steal the television set and found out it was already stolen.'”

Quote of the movie: “Pirates of Silicon Valley” – Microsoft steals from Apple

In June of 1985, Bill Gates sent a remarkable memo to both the then-CEO of Apple, John Sculley, and then-head of Macintosh development, Jean Louis Gassée, and urged them to spread their wings by licensing their hardware and operating system to other companies.

Apple must make Macintosh a standard. But no personal computer company, not even IBM, can create a standard without independent support. Even though Apple realized this, they have not been able to gain the independent support required to be perceived as a standard.

Apple ignored his advice.

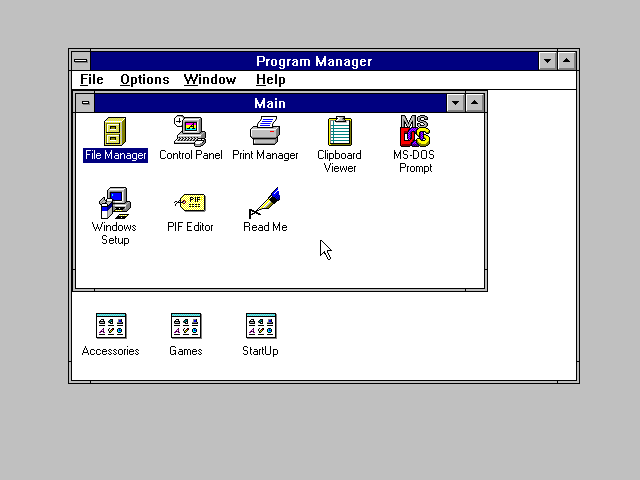

Five months after he sent the memo, Windows 1.0 was released. Microsoft’s decision to do exactly as Gates had recommended to Apple resulted in market domination. If Apple had taken Gates’ advice, things could have been very different.

Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak has since said:

“The computer was never the problem. The company’s strategy was. Apple saw itself as a hardware company; in order to protect our hardware profits, we didn’t license our operating system. We had the most beautiful operating system, but to get it you had to buy our hardware at twice the price. That was a mistake. What we should have done was calculate an appropriate price to license the operating system. We were also naive to think that the best technology would prevail. It often doesn’t.”

(Source: Great Business Letters)

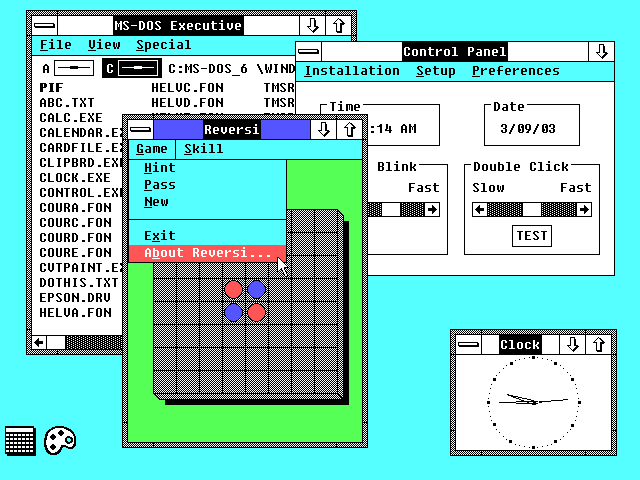

Windows 1.01 was based on DOS and was incredibly slow, but it reminded one of the Macintosh GUI in some features. In order to prevent Apple from taking legal action, Gates put the screws on Apple boss Sculley. His message was: As soon as Apple sends out the lawyers, Microsoft will immediately stop the development of Word and Excel for the Mac. Since Apple was depending on the Microsoft applications, Sculley licensed some of the Mac technologies to Microsoft.

As Microsoft went public with the next large version leap of Windows 2.03 at the beginning of 1988, Sculley tried to pull the ripcord and sued Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard for copyright infringement on March 17, 1988. John Sculley had been in a difficult situation, particularly as he had engaged in vague formulations in the contract with Microsoft in 1985, which gave great leeway to Gates and his lot. Moreover, he knew that his chances to win an action against Microsoft had been, purely from a legal viewpoint, not particularly good: “The look and feel, which is how it looks, the experience of using it, was not patentable, but it was copyrightable, but there was no precedent law. This was going to be a precedent-setting case.”

Parody of an advertising spot for Windows featuring Steve BallmerBill Gates recalls also reluctant this time.: “But it was a period of five years where, Microsoft er, our whole strategy would have been ruined because Windows was very important to us. (…) We assumed that the lawyers, the judges would all come to the right conclusion which eventually they did.” Sculley: “And Apple lost. But in that period of about six years that this case was going on it may have lulled us into a bit of complacency thinking that we were going to be insulated, you know, from the Windows attack.”

The introduction of Windows 3.1 in 1992 brought Microsoft the breakthrough in the “GUI war”. The system lacked the elegance and usability of the Macintosh system 7.0, but Windows appeared good enough to most PC users. With the help of Windows 95, which had been introduced with gigantic effort on August 24, 1995, Microsoft caught up closer to the Mac and in some aspects even appeared more progressive than the Mac OS, which had become dated in the meantime.

Steve Jobs, who, as the head of NeXT, had observed the advance of Windows from a distance, did not have any kind words for Bill Gates at the launch of Windows 95:

The only problem with Microsoft is they just have no taste, they have absolutely no taste, and what that means is – I don’t mean that in a small way, I mean that in a big way. In the sense that they don’t think of original ideas and they don’t bring much culture into their product, and you say why is that important – well you know proportionally spaced fonts come from type setting and beautiful books, that’s where one gets the idea – if it weren’t for the Mac, they would never have that in their products and so I guess I am saddened, not by Microsoft’s success – I have no problem with their success, they’ve earned their success for the most part. I have a problem with the fact that they just make really third rate products.

It is claimed that Jobs has apologized to Bill Gates for this remark later.

Steve Jobs about Microsoft (1995)

The relationship between Apple and Microsoft – and thus also between Steve Jobs and Bill Gates – did not get back to normal before the summer of 1997, when Steve Jobs returned to Apple and engaged in the support of Microsoft to make the troubled company profitable again.

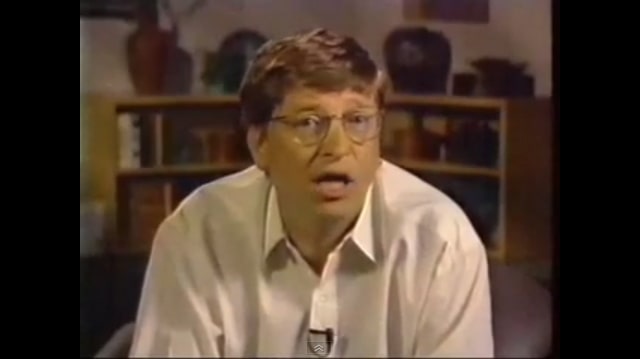

Bill Gates on the video screen at the MacWorld Expo 1997 in Boston

Many faithful Apple fans still remember with horror the moment when Steve Jobs announced the former archrival very pragmatically as the knight in shining armor at the MacWorld Expo 1997 in Boston with Bill Gates appearing on an oversized video screen just like “Big Brother.” Introducing Gates, Jobs said: “We have to let go of the notion that in order to for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose. Relationships that are destructive don’t help anybody. The era of setting this up as a competition between Apple and Microsoft is over.”

According to certain rumors, Microsoft invested 150 million dollars in 150,000 Apple stocks and paid another 100 million dollars for copyright infringement over the past few years. At the same time, Gates obliged himself to continue the development of the Internet Explorer and Microsoft Office for the Mac for the following five years. Gates drew hisses from the audience of Apple faithful. The crowd also groaned when Steve Jobs said Apple would make Microsoft’s Internet Explorer the default browser for viewing the World Wide Web on Macintosh computers. That development was a blow to Netscape Communications Corp., which made a more popular competing browser and lost later on in the famous “browser war” against Microsoft.

In October 2015 Steve Ballmer appeared on Bloomberg TV where the former executive briefly touched on Microsoft’s monumental 1997 investment in Apple.

At the time, Microsoft’s deal with Apple not only helped rescue the company from the brink of bankruptcy, it gave Apple a much-needed lifeline, affording the company room and time to innovate. And as we all know, the deal ultimately helped set Apple up for the most astounding tech resurgence in history.

In 2010 – after a stunning comeback – Apple Inc. overtook Microsoft Corp. to become the most valuable technology company on optimism it can keep adding customers for its iPhone, Macintosh computer, and iPad. On May 26th by 4 p.m. New York time in Nasdaq Stock Market trading, Apple’s market value was at $222.1 billion, higher than Microsoft’s $219.2 billion. That made Apple the most valuable technology firm in the world.

In an interview with Kara Swisher and Walt Mossberg from the Wall Street Journal, Apple CEO Steve Jobs downplayed the significance of Apple’s passing Microsoft in market value. “For those of us who have been in the industry a long time, it’s surreal,” Jobs said. “But it doesn’t matter very much, it’s not what’s important.

“It’s not why any of our customers buy our products. So I think it’s good for us to keep that in mind.”

“They just don’t get it.” That’s how Steve Jobs described his digital rivals Microsoft and Google in an interview with his biographer Walter Isaacson.

For his biography, “Steve Jobs,” Isaacson conducted more than 40 taped interviews with the Apple co-founder and CEO – all of them done while Apple was on its ascent with one great product after another, but Jobs was on his decline, ill with a form of pancreatic cancer that would end his life at age 56.

Update:

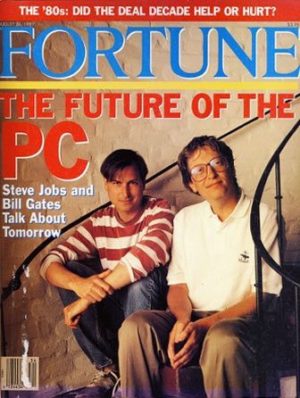

JOBS AND GATES TOGETHER

The boy wonders of computing, now thirtysomething, argue over where innovation comes from and where PCs will go.

By Steven P. Jobs, William H. Gates III, Brenton R. Schlender

August 26, 1991

(FORTUNE Magazine) – The two college dropouts most responsible for unleashing the PC revolution rarely see each other anymore, though they say that they’re still friends. At FORTUNE’s invitation, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs met for a Sunday evening in late July to discuss the prospects for the tumultuous industry they shaped. Gates, 35, left Harvard in 1975 to co-found Microsoft. His big break came in 1980, when IBM asked him to provide the operating system — the program that manages a computer’s inner workings — for its now famous PC.

Jobs, 36, who left Reed College to sojourn in India, is best known for co-founding Apple Computer. He led the development of the Macintosh, a computer much easier to use than IBM’s somewhat nerdy PC. Gates has imitated many features of the Mac’s software with a popular PC program called Windows.

Since the mid-1980s the men have taken dramatically different paths. Gates, who owns more than $4 billion of Microsoft stock, remains a workaholic bachelor and an omnivorous reader — he has read several biographies of Napoleon. He has built Microsoft into the world’s largest and most profitable PC software company. It hasn’t all been rosy. Microsoft’s relationship with IBM soured this year, mainly because the two couldn’t agree on an operating- system strategy for future PCs. And the Federal Trade Commission recently began investigating Microsoft’s practices.

Jobs has been less visible but just as busy. In 1985 he started Next, aiming to build the personal computer of the 1990s. Next’s first machine appeared two years ago. Its basic software, NextStep, makes the machine unusually easy to customize; IBM was so impressed it licensed NextStep for its own computers. Despite the dazzling technology, the going has been slow at Next. For one thing, IBM never put NextStep on the market. But lately business has picked up — 10,000 systems rolled out of Next’s automated plant during the second quarter. Jobs has other reasons to smile. He and wife Laurene, who married earlier this year, are expecting their first child in September.

FORTUNE associate editor Brenton R. Schlender put the questions at the meeting. Beneath the conviviality, Jobs and Gates each had a business objective. Jobs lobbied for Gates to develop software for the Next computer. And Gates, whose company is being sued by Apple for allegedly pirating Macintosh software features, was hoping to learn more about the product’s origin.

Schlender: What did you think when the PC appeared ten years ago?

Jobs: When IBM entered the market, we did not take it seriously enough. It was a pretty heady time at Apple. We were shipping tens of thousands of machines a month — more computers than IBM was total. Even so, a lot of people think IBM invented the personal computer, which of course isn’t true.

Gates: A lot of people think Apple did, and that isn’t true either. Our first program was for the Altair ((a mail-order kit sold in 1975)).

Schlender: Does Microsoft’s control of PC operating systems stifle competition in the industry?

Gates: There’s not one element of the industry that’s not competitive. There are people who are cloning Intel’s chips; there are people who are cloning my operating system; there are many, many people who make PCs; and for every software application there are lots of people competing. There is no competitive imperfection.

Jobs: How come nobody has successfully competed with you? I’m not accusing you or Microsoft of anything. I’m not even saying it’s necessarily bad. I’m just saying it’s an interesting contrast. When I zoom back and look at this, there are hundreds of people making PCs, and hundreds of people writing applications programs for them.

Gates: Right.

Jobs: But they all have to travel through this very small orifice called Microsoft to get to one another.

Gates: It’s a very large orifice! ((Laughs.))

Jobs: But it’s only one company.

Gates: Are you saying there’s something wrong with our popularity? My approach to the PC market has been the same from the very beginning. The goal of Microsoft is to create the standard for the industry. Nothing has changed.

Schlender: What does the future hold for IBM and Apple? What do you think of their decision to collaborate on PC software?

Gates: It’s surprising to me.

Jobs: Yes, we are confused about that.

Gates: ((Apple President)) Mike Spindler has said they want to turn Apple into more of a software company. If that’s your goal, you don’t go and give the half of the company that is the future of Apple software to a joint venture. What is Apple getting in return? Here’s the part I don’t understand: What is the contribution from IBM? The IBM name? Did Apple feel so bad about their own work that they had to have that?

Jobs: I truly believe the challenge for IBM is that they can’t survive by selling the same thing you can buy from somebody else for 30% less money. Their cost structure doesn’t allow them to compete with companies that don’t do massive amounts of R&D, that don’t have twice as many employees as they need, et cetera, et cetera. So IBM has to do one of two things: One, suffer continuous erosion of its market share until eventually it goes out of business, which I hope doesn’t happen. Or two, come up with some way to add value. In my opinion the way to make your machines unique is with unique software.

Gates: I said that back in the Seventies! ((Laughs.)) There’s something else I don’t understand. If IBM already held a license to your NextStep software, why did they get all this going with Apple rather than just come to you and expand their license?

Jobs: I really want to answer this que

stion, but I’ve got to be careful what I say. It’s not my purpose to alienate anyone at IBM.

Gates: We share this interest. ((Both laugh.))

Jobs: Somebody at IBM a few years ago saw our NextStep operating system as a potential diamond to solve their biggest and most profound problem, that of adding value to their computers with unique software. Unfortunately, as I learned, IBM is not a monolith. It is a very large place with lots of faces, and they all play musical chairs. Somewhere along the line this diamond got dropped in the mud, and now it’s sitting on somebody’s desk who thinks it’s a dirt clod. Inside that dirt clod is still a diamond, but they don’t see it.

Schlender: Is the PC industry, which until now has been dominated by American companies, liable to get overrun by the Japanese?

Jobs: Computer companies fall on a spectrum of enthusiasm for manufacturing. On the left end are companies that look at manufacturing as a necessary evil, who wish they didn’t have to do it. And at the far right you have people who look at manufacturing as a competitive advantage. Clearly a lot of the Japanese companies look at themselves that way. Unfortunately a lot of American companies look at manufacturing as a necessary evil. You can say the same thing about the way they see software. My opinion is that the only two computer companies that are software-driven are Apple and Next, and I wonder about Apple. Most computer companies would rather that software didn’t even exist.

Gates: Good!

Jobs: It’s good for Microsoft today. But unfortunately all those companies could give way to Japanese companies a few years down the road.

Gates: I think you give up too easily on Americans. You pick one dimension . . .

Jobs: I focus on manufacturing because I care about it. I’ve seen IBM’s. I built Apple’s and Next’s, and I know what Sun does. Ultimately, I believe that most of the PCs will come from offshore. We’re just not good enough at manufacturing.Where will the key innovations come from? Established giants like Microsoft or upstarts like Next?

Gates: I contend technology breakthroughs can happen by extending what we already have. Let’s take handwriting computers. The hardware is coming from PC-compatible makers like Dell Computer ((of Austin, Texas)) and NCR and some Japanese companies. The software will come either from Microsoft or from a U.S. competitor named Go Corp. ((of Foster City, California)). That’s going to be a major breakthrough, and who do you give credit to?

Jobs: I think everybody gives credit to Go, but Go will be crushed.

Gates: That’s one of the nastiest comments I’ve ever heard. I’ve been working on handwriting since long before there ever was a Go Corp.

Jobs: Really? I didn’t know that. Most people would say that Go is the company that first tried to commercialize that technology.,

Gates: Well, Go hasn’t shipped anything yet, and I’ll ship my stuff before they ship theirs.

Jobs: My experience has been that creating a compelling new technology is so much harder than you think it will be that you’re almost dead when you get to the other shore. That’s why, when you take big leaps, like the Mac, or object- oriented programming, or handwriting recognition, you have to leave old technology behind. When Lindbergh was going to fly from New York to Paris, he had to decide what to take with him. There were a lot of demands. They fell into two categories — things that would make his journey safer or more comfortable, and things that would increase his chances of making it to Paris. Weight was a real problem. He could take more gas, which would increase his safety, or he could take a compass, which would increase his chances of getting to Paris. Every time he came down on the side of increasing his chances of getting to Paris at the sacrifice of safety or comfort. That’s why he made it.

Gates: Smart people like Steve ought to try to build things from scratch. That’s a worthy thing. But every time it should be a test. Right now there’s a test in handwriting PCs, in object-oriented operating systems, in multimedia computers. Those are the big questions for personal computing in the 1990s, and I’m the one who has to prove the validity of the evolutionary approach.

Jobs: It’s true, your evolutionary approach with Windows is bringing to PCs great new technologies that Apple and others pioneered. But in the meantime — and it’s been seven years since the Macintosh was introduced — I still think that tens of millions of PC owners needlessly use a computer that is far less good than it should be.

[…] Microsoft’s Relationship with Apple […]

[…] del debutto di Windows 95, Steve Jobs, che ai tempi non era ad Apple per note vicende, aveva dichiarato: “L’unico problema con Microsoft è che non hanno stile, non hanno assolutamente stile. E […]

[…] del debutto di Windows 95, Steve Jobs, che ai tempi non era ad Apple per note vicende, aveva dichiarato: “L’unico problema con Microsoft è che non hanno stile, non hanno assolutamente stile. E […]

[…] del debutto di Windows 95, Steve Jobs, che ai tempi non era ad Apple per note vicende, aveva dichiarato: “L’unico problema con Microsoft è che non hanno stile, non hanno assolutamente stile. E […]

[…] Did Bill Gates work for Apple? […]

[…] sitio Mac-History.net La cita como un ejemplo del momento en que Apple y Microsoft pasaron de aliados a rivales, en un […]