“The demo was not going well. Again. It was a late morning in the fall of 2006. Almost a year earlier, Steve Jobs had tasked about 200 of Apple’s top engineers with creating the iPhone. Yet here, in Apple’s boardroom, it was clear that the prototype was still a disaster. It wasn’t just buggy, it flat out didn’t work. The phone dropped calls constantly, the battery stopped charging before it was full, data and applications routinely became corrupted and unusable. The list of problems seemed endless. At the end of the demo, Jobs fixed the dozen or so people in the room with a level stare and said, «We don’t have a product yet.»

So starts Fred Vogelstein’s article in the U.S. technology magazine «Wired» (Feb. 2008) about the difficult launch of a product that would later turn the mobile phone industry upside down. Vogelstein is known for his well-researched reports and features. For example, he revealed (also for Wired) that the story of how the social network Facebook came into being was somewhat different than founder Mark Zuckerberg had repeatedly claimed.

For the «Untold Story» in Wired about the creation of the iPhone – a story that no one had told before – Fred Vogelstein interviewed countless actors and observers and was able to report on exciting details on this basis: Apple CEO Steve Jobs, for example, did not attack his employees screaming after the failed demo in the fall of 2006 – as he had done so many times before. This time, he remained completely calm. The silence made the panel even more nervous than a tantrum from Jobs. «That was one of the few times at Apple that a cold shiver went down my spine,» said one meeting attendee.

The iPhone’s back story goes back to 2002. Shortly after the unveiling of the first iPod, Apple executives were specifically looking at whether Apple should develop a (mobile) phone. Jobs realized early on that the boom in Blackberry smartphones in large companies in the USA would sooner or later spread to private customers. It was also foreseeable to him that the cell phones of the future would usually have an MP3 player built-in, so the dominance of the iPod as a mobile music player seemed threatened.

In the short term, however, Apple was not in a position to build a smartphone itself at the time. The iPod’s operating system was not made to handle complicated network operations or elaborate graphics. And no slim version of the Macintosh operating system OS X existed at the time that could have run on the phone chips available at the time.

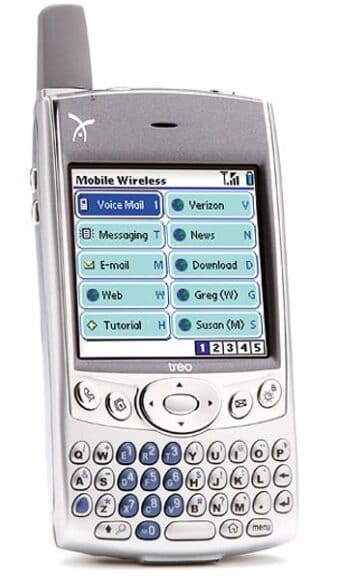

In particular, the sales success of the Palm Treo 600, which combined the functions of a cell phone, PDA and Blackberry, encouraged Steve Jobs in his intention to become active in the market for so-called convergence devices himself. In 2004, the iPod business already contributed to 16 percent of Apple’s revenue. But new developments such as the growing popularity of 3G cell phones and WiFi phones, as well as falling memory prices, were at least potentially threatening the iPod’s leadership position. In addition, new online music platforms were constantly being established to compete with Apple’s iTunes Store.

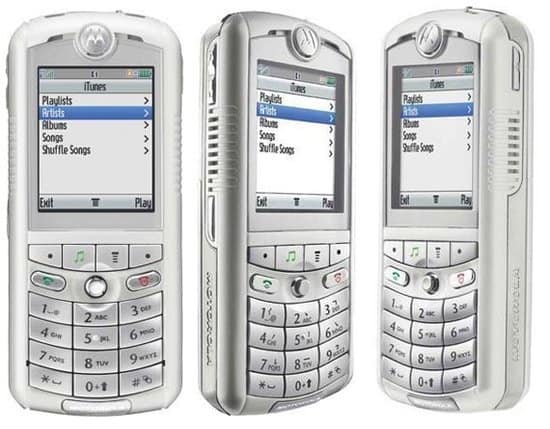

Quick action was now necessary, even though Apple itself was not yet ready for the development of an iPhone. In the search for cooperation partners, Steve Jobs chose Motorola. The U.S. mobile phone giant was celebrating great sales successes at the time with its RAZR design cell phone. Jobs also knew Motorola CEO Ed Zander from the time when Zander had worked in the top management of Sun Microsystems. The scenario called for Apple to concentrate fully on developing the music software, while Motorola and cellular provider Cingular would take care of the hardware and complicated network technology.

Jobs expected a worthy successor to the RAZR from Motorola, but was bitterly disappointed: Motorola didn’t present a new design gem, but only slightly modified the existing E398 model. The iTunes-compatible phone could only hold 100 songs. The music tracks could only be transferred to the cell phone via a PC. And on top of that, the ROKR E1 was extremely ugly in Steve Jobs’ eyes.

At the presentation of the Motorola ROKR E1 in September 2005, the Apple CEO made little effort to conceal his lack of enthusiasm for the first iTunes cell phone. Jobs coolly described it at the event as «an iPod shuffle on a cell phone» – and already suspected that the ROKR would be left behind by buyers. At that point, he was already pursuing completely different plans, namely to build his own music phone and to stop compromising with handset manufacturers or network operators.

According to Vogelstein’s research, Jobs met with a handful of Cingular executives as early as February 2005 to discuss a partnership without Motorola. The panel included Cingular CEO Stan Sigman, who would be in charge of AT&T’s wireless business after Cingular was acquired by AT&T in December 1996. In the meeting, Steve Jobs made three things clear. Apple has the technology to build a revolutionary device. Apple is willing to enter into an exclusive agreement with a wireless provider. And – in the event that no provider takes up this business model – Apple is also prepared to enter the market itself as a virtual network provider and compete with the established carriers.

Compared to the situation in 2004, Apple had much better starting conditions for building its own smartphone at that time: As part of the secret work on an Apple tablet PC, the engineers in Cupertino had built up considerable knowledge of touchscreen technology that could also be transferred to a small device. In addition, with the ARM-11 chip, a microprocessor was finally on the market that could give a cell phone the necessary power for sophisticated smartphone and iPod applications. Furthermore, companies such as the British Virgin Group had proven that it was possible to earn money as a virtual network operator without having to operate transmission towers.

In the twelve months of negotiations with Cingular, Apple succeeded in doing nothing less than turning the established business model between cell phone producers and network operators on its head. In the era before the iPhone, providers alone determined the conditions under which services were offered in their network. The cell phones played only a minor role in this scenario and were also usually offered to consumers at absurdly low symbol prices. The subsidized cell phones were ultimately refinanced through long contract terms of the cell phone customers. This model worked quite well as long as the one-dollar or one-euro cell phones constantly attracted new customers who had not previously had a mobile communications contract. In cutthroat competition, however, low-cost cell phones were no longer enough to retain customers over the long term.

For ages, Apple’s recipe for success has included an almost paranoid secrecy associated with every new product. And with the iPhone, Steve Jobs personally made sure that the usual security precautions were once again tightened. Internally, the iPhone project was just called Purple 2 or P2. Jobs spread the development teams across the entire Apple campus in Cupertino so that no one could get an idea of the overall strength of the project team.

When Apple employees went to Cingular, they posed as Infineon employees, Wired reporter Vogelstein found out. The German chip company supplies the radio component of the iPhone. Jobs even made sure that hardly anyone within Apple got to see the overall concept of the iPhone. The hardware team had no idea what the user interface would look like until shortly before the iPhone was unveiled at MacWorld Expo in January 2007. Their dummy devices were loaded with fake software that had nothing to do with the eventual iPhone. And the software people were handed clumsy wooden boxes that ran their programs. According to Vogelstein’s research, only about 30 top people in the project were allowed to see the complete iPhone before MacWorld 2007.

The secrecy did not stop after the launch of the iPhone. Until today the details of the revenue sharing between AT&T and Apple are secret. However, analysts such as Gene Munster of Piper Jaffray, after analyzing the balance sheets, assume that Apple receives around 18 US dollars per month from AT&T for each iPhone customer. If this figure is realistic, Apple will take another $432 in commission over the course of the minimum contract period of 24 months, in addition to the hardware price of $399. It’s no wonder that cell phone manufacturers like Nokia and SonyEricsson looked to California with disbelief and envy – and providers like Vodafone now fear that the iPhone example will now set a precedent for other top cell phones.

Later, the head of Deutsche Telekom, René Obermann, found himself in a similar position to Cingular and AT&T in 2006. For Obermann, the sex appeal of the iPhone offered a unique opportunity to distract from the gray reality at T-Mobile and the entire Telekom Group. For this reason, Obermann also accepted conditions that he would otherwise not have accepted from any other cell phone manufacturer.

AT&T and T-Mobile wanted the iPhone in their product portfolios. Absolutely. They also respected the immense effort Apple had put into developing the iPhone. For example, Apple spent several million dollars on the purchase of equipment for antenna and network tests alone. In total, the development of the iPhone is said to have cost around 150 million dollars. At least in the U.S., the formula for business success with the iPhone worked. In the first 200 days, Apple sold four million iPhones, Apple CEO Steve Jobs announced at the MacWorld Expo. According to a study by Canalys, the iPhone already captured third place in the «smart mobile devices» category in the 4th quarter of 2007 with a market share of 6.5 percent, behind Nokia (53 percent) and Blackberry manufacturer Research In Motion (11.4 %). This means that the iPhone was able to overtake other smartphone manufacturers such as Motorola, SonyEricsson, and Windows Mobile licensees such as HTC and Samsung right from the start. However, smartphones only account for a small fraction of the mobile phone market, which is worth billions.

Market success in Germany was more modest. In the first eleven weeks, T-Mobile sold just 70,000 iPhones, while in the U.S. an average of 20,000 devices crossed the counter every day. However, there are also many iPhone buyers in Germany who do not appear in any T-Mobile statistics because they acquired their dream phone on the gray market on the Internet or on a trip to the USA. Experts believe that one in four iPhones sold in the U.S. was not registered with AT&T.